The Psychological and Mythological Dimensions of Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir

A Journey into the Archetypes of Human Experience

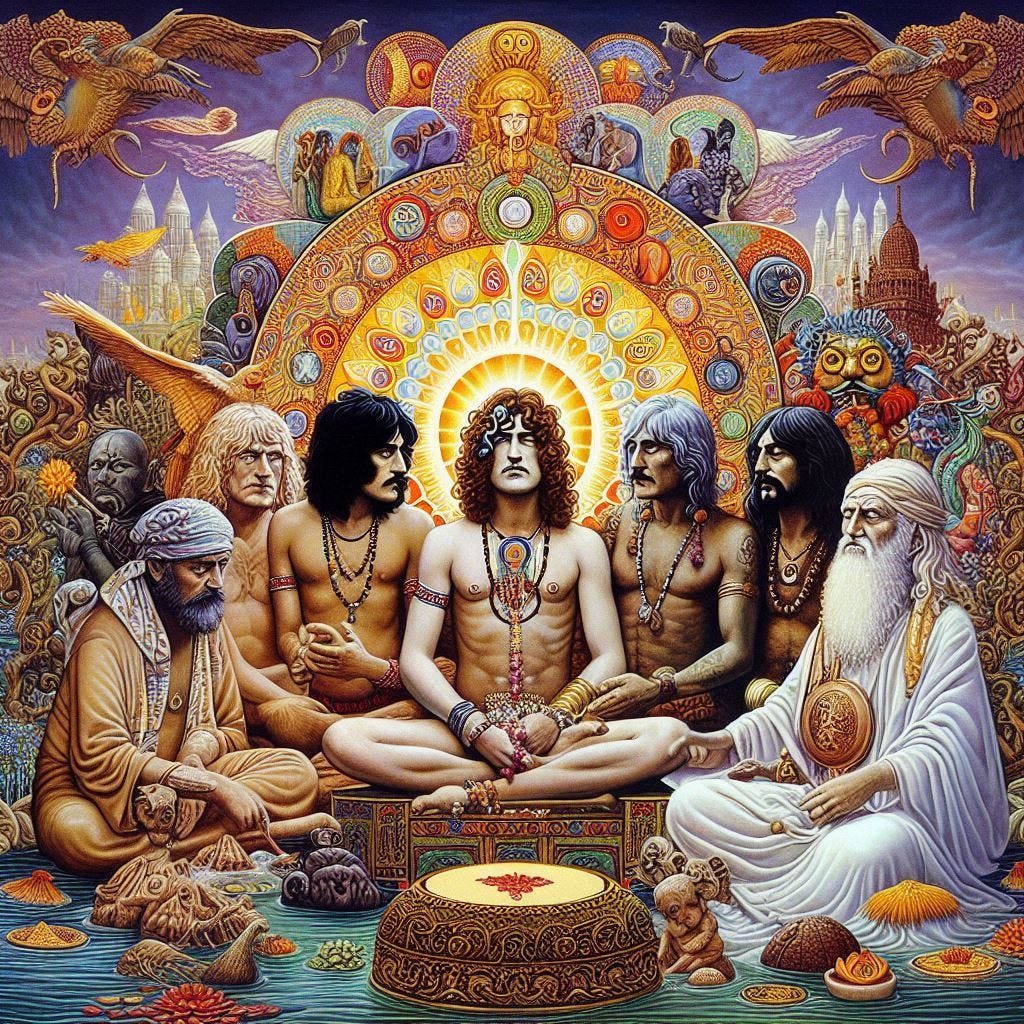

This article explores the psychological and mythological dimensions embedded within Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir. The song, widely regarded as an epic blend of rock and Eastern musical influences, invites listeners into a journey that transcends the personal to touch upon universal human experiences. Drawing from Carl Jung’s archetypal theory, Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, and Eastern philosophical traditions, Kashmir serves as a conduit for exploring themes of transcendence, unity with nature, and the hero’s journey. This article examines how the song’s composition, symbolism, and lyrics mirror deeply ingrained psychological patterns and mythological structures, offering a narrative that resonates with collective unconscious experiences of human exploration, spiritual seeking, and personal transformation.

Introduction

Music is one of the most powerful mediums through which the human psyche expresses itself. It has the ability not only to evoke emotion but also to act as a vessel for complex psychological and mythological symbols. Certain songs, particularly, capture the imagination by embodying archetypal elements that speak directly to the collective unconscious. Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir, released in 1975 on the album Physical Graffiti, is one such song. It takes listeners on a journey across physical and metaphysical landscapes, exploring themes of time, space, nature, and spiritual longing. Its grandiosity and mysticism have cemented it as a cultural touchstone, not only in rock music but also in its capacity to resonate with universal human experiences.

Kashmir stands out in Led Zeppelin’s discography for its unique blend of Western rock, orchestral elements, and Eastern musical influences. The song’s repetitive, trance-like rhythm contributes to its hypnotic and ritualistic quality. Robert Plant’s lyrics evoke an epic journey across vast deserts and mystical realms, which mirror the internal psychological and spiritual journey of the listener.

This article analyzes Kashmir from a psychological and mythological perspective, exploring how its themes resonate with Jungian archetypes, Campbell’s hero’s journey, and Eastern philosophical concepts of transcendence and unity. Ultimately, Kashmir is more than mere entertainment; it is a portal to deeper questions of existence, purpose, and personal transformation.

Archetypal Themes: The Wanderer and the Hero’s Journey

At the core of Kashmir is the archetype of the wanderer, a symbol deeply rooted in mythology, religion, and psychology. Carl Jung (1959) defined archetypes as universal symbols that emerge from the collective unconscious, manifesting in cultural narratives, dreams, and personal experiences. The wanderer or traveler is a central figure in these stories—one who embarks on a journey of self-discovery, spiritual growth, or transformation. In Kashmir, this journey is illustrated through the lyrics, which describe a traveler navigating hostile and mysterious environments, echoing mythological heroes like Odysseus in The Odyssey or Moses during the exodus.

The hero’s journey, as outlined by Joseph Campbell (1949) in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, is a recurring narrative structure in mythologies across cultures. It involves the hero’s departure from the known world, a series of trials or initiations, and their return, transformed by their experiences. Kashmir parallels this structure, presenting a journey that begins in isolation and hardship, with the promise of eventual enlightenment and transcendence.

The refrain, “Let me take you there,” invites the listener on this journey—not only a physical one but also a psychological one, guiding them into the depths of the unconscious. The wanderer’s journey through foreign landscapes reflects the emotional and psychological territory individuals navigate during periods of personal crisis or transformation, suggesting that the meaning of the journey lies in the process of discovery rather than the destination.

Nature and Transcendence

In Kashmir, nature is more than a backdrop; it symbolizes broader themes of transcendence and unity with the universe. The recurring imagery of deserts, mountains, and oceans evokes both isolation and awe, representing the smallness of the individual in contrast to the vastness of existence. From a Jungian perspective, nature often symbolizes the unconscious, with its boundless mysteries and unpredictable forces. The wanderer’s journey through these landscapes can be interpreted as an encounter with the unconscious, where they must confront repressed and unknown elements of the self.

The lyrics “Oh, let the sun beat down upon my face, stars to fill my dream” suggest a moment of surrender to nature’s overwhelming power—a key element of transcendental experiences. In Eastern philosophies such as Buddhism and Hinduism, transcendence involves moving beyond the limitations of the ego to achieve unity with the cosmos. Kashmir reflects this through its expansive soundscape and invocation of natural forces, dwarfing human concerns and inviting listeners to connect with something larger than themselves.

This surrender to nature reflects what Abraham Maslow (1964) described as peak experiences—moments of deep harmony, purpose, and interconnectedness with the world. These experiences dissolve the ego, allowing individuals to feel at one with the universe. The hypnotic rhythm and mystical lyrics of Kashmir create an aural environment conducive to such transcendental states, encouraging listeners to lose themselves in the journey.

Temporal Fluidity and the Eternal Present

Kashmir also explores the fluidity of time, with the lyric “I am a traveler of both time and space” reflecting a departure from linear time. This resonates with the concept of cyclical time in Eastern traditions, where existence is viewed as an eternal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. In Hinduism, for example, time is seen as a repeating cycle, mirroring psychological processes of growth, transformation, and renewal.

Psychologically, this temporal fluidity can also be linked to Carl Jung’s concept of synchronicity, where meaningful coincidences occur outside the bounds of causality (Jung, 1960). The traveler in Kashmir, navigating both time and space, reflects this idea of interconnected experiences and the cyclical nature of personal growth. The song’s rhythmic shifts between intense and subdued moments further mirror the cycle of action, reflection, and renewal.

Mythological Landscapes: Between the Known and the Unknown

The landscapes described in Kashmir—vast deserts, endless seas, and ancient realms—symbolize the mythological ‘unknown,’ a realm the hero must navigate in their journey toward self-realization. Deserts often represent desolation and trial in mythology, places where heroes confront their innermost fears and are stripped of external comforts.

The recurring refrain “Let me take you there” suggests the presence of a guide or mentor, a figure who appears in mythological stories to help the hero navigate the unknown. In Kashmir, the music itself becomes the guide, leading listeners through this sonic landscape and inviting them to confront their own psychological challenges.

Conclusion

Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir is a monumental work that taps into deep psychological and mythological themes. Its hypnotic rhythm, expansive soundscape, and mystical lyrics transport listeners on a journey through time and space, exploring both the physical world and the inner landscapes of the psyche. Through the lens of Jungian psychology, Campbell’s hero’s journey, and Eastern philosophies of transcendence, Kashmir emerges as a modern myth that speaks to universal human experiences of longing, struggle, and transformation.

By engaging with these archetypal elements, Kashmir transcends the boundaries of music, becoming a vessel for exploring profound questions of existence and meaning. Its enduring appeal lies in its ability to evoke both the external and internal journey, reminding us that the path to enlightenment is one we all must walk—across the deserts of our minds and the mountains of our souls.

References

Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1960). Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle. Princeton University Press.

Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, Values, and Peak Experiences. Ohio State University Press.

Bet you didn't know Kashmir is my favorite song of all time.